Information Literacy Modules

- About the Modules

- Forming Your Research Question

- Searching for Information Online

- Advanced Searching

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources

- Scholarly Articles

- Information Cycles and Communication Sources

- Misinformation and Media Bias

- Organizing Sources

- Academic Integrity

- Understanding Plagiarism & Citing Sources

- Copyright, Fair Use, & Public Domain

- Literature Reviews

- Scholarly Conversation

Information Cycles and Communication Sources

Introduction

(Viktor Bystrov, Unsplash)

Information is delivered to us over time in a variety of ways and categorized in a variety of genres. Each information source is intended for a specific audience and uses unique conventions to target its audience; each source also follows a specific timeline. Three broad categories you will come across often during the research process are popular communication, trade communication, and scholarly communication.

This module explains the differences between popular, trade, and scholarly sources.

Learning Outcomes

After completing this module, you will be able to:

- Understand the cycle of information.

- Recognize patterns in Information Cycles.

- Differentiate between scholarly, trade, and popular communication.

- Identify which resources are best for research, and

- Use techniques for finding peer-reviewed articles.

Making Sense of Information

We take in so much information in so many different forms every day that it's hard to make sense of it all. In extreme cases, we may even experience "information overload".

To make your source selection process more effective and efficient, it's important to understand that information is produced and distributed according to general patterns, often referred to as "Information Cycles". A skilled researcher who understands these patterns and knows which types of information sources are most appropriate for any given project is likely to achieve consistent success in finding what they need.

The Day of an Event

Television, The Internet, and Radio

(John Tuesday, Unsplash)

The information:

- Is primarily provided through up-to-the-minute resources like broadcast news, internet news sites, and news radio programs.

- Is quick, generally not detailed, and regularly updated.

- Explains the who, what, when, and where of an event.

- Can, on occasion, be inaccurate.

- Is written by authors who are primarily journalists.

- Is intended for a general audience.

The Day After an Event

Newspapers

(Annie Spratt, Unsplash)

The information:

- Is longer as newspaper articles begin to apply a chronology to an event and explain why the event occurred.

- Is more factual and provides a deeper investigation into the immediate context of events.

- Includes quotes from government officials and experts.

- May include statistics, photographs, and editorial coverage.

- Can include local perspectives on a story.

- Is written by authors who are primarily journalists.

- Is intended for a general audience.

The Week of or Weeks After an Event

Weekly Popular Magazines and News Magazines

(Charisse Kenion, Unsplash)

The information:

- Is contained in long-form stories. Weekly magazines begin to discuss the impact of an event on society, culture, and public policy.

- Includes a detailed analysis of events and interviews, as well as opinions and analysis.

- Offers perspectives on an event from particular groups or is geared towards specific audiences.

- While often factual, information can reflect the editorial bias of a publication.

- Is written by a range of authors, from professional journalists to essayists to scholars or experts in the field.

- Is intended for a general audience or specific nonprofessional groups.

Six Months to a Year After an Event and On...

Academic Journals

(Annie Spratt, Unsplash)

The information:

- Includes detailed analysis, empirical research reports, and learned commentary related to the event.

- Is often theoretical, carefully analyzing the impact of the event on society, culture, and public policy.

- Is peer-reviewed. This editorial process ensures high credibility and accuracy.

- Is often narrow in topic.

- Is written in a highly technical language.

- Includes detailed bibliographies.

- Is authored by scholars, researchers, and professionals, often with Ph.D's.

- Is intended for other scholars, researchers, professionals, and university students in the field.

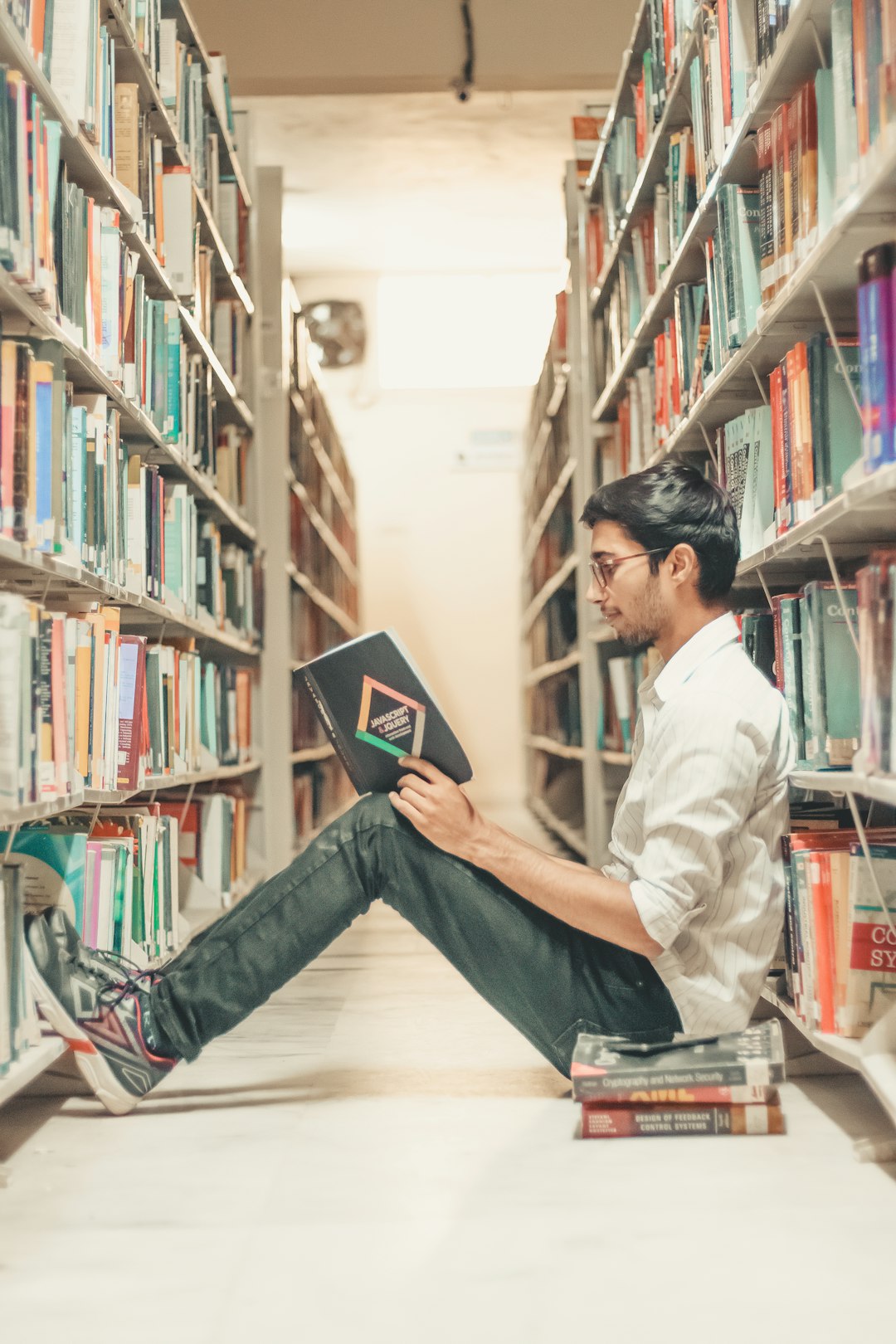

A Year to Years After an Event and On...

Books

(Dollar Gill, Unsplash)

The information:

- Provides in-depth coverage of an event, often expanding and detailing themes, subjects, and analysis begun in academic research and published in journals.

- Often places an event into some sort of historical context.

- Can provide broad overviews of an event.

- Can range from scholarly in-depth analysis of a topic to popular books that provide general discussions and are not as well-researched.

- Might have a bias or slant, but this is dependent on the author.

- Includes bibliographies.

- Is often written by scholars, specialists, researchers, and professionals, though the credentials of authors vary.

- Can be intended for a broad audience depending on the book, ranging from scholars to a general audience.

Government Reports

(Giorgio Tomassetti, Unsplash)

The information:

- Comes from all levels of government, including from state, federal, and international governments.

- Includes reports compiled by governmental organizations and summaries of government-funded research.

- Is factual, often including statistical analysis.

- Often focuses on an event about public policy and legislation.

- Is authored by governmental panels, organizations, and committees.

- Is intended for all audiences.

Reference Material

The information:

- Is considered established knowledge.

- Is published years after an event takes place in encyclopedias, dictionaries, textbooks, and handbooks.

- Includes factual information, often in the form of overviews and summaries of an event.

- May include statistics and bibliographies.

- Is often not as detailed as books or journal articles.

- Is authored by scholars and specialists.

- Is often intended for a general audience, but may be of use to researchers, scholars, or professionals.

General Background Information

Most of the information from the Information Lifecycle that is produced in 6 months or less is best used when you are at the very beginning of your research. General background information helps you generate ideas, ask questions, and identify potential topics. Since you are not yet sure what you want to write about, browsing for as many ideas as you can find is key. You want to review a lot of information in a short period of time just to find out what interests you.

Expert Research is Vetted

You might have heard of the idea of the "vetting process", often within the context of a news media story. "Vetting" refers to the effort to verify that the information is accurate and ready to be released to the public for use and application.

If a media outlet moves too quickly to release a story before the vetting process is complete, the information is at risk for not being accurate and complete. Media outlets competing for a breaking story might try to predict the outcome of a presidential election or an important court decision only to realize that the actual outcome was exactly the opposite.

After brainstorming to find a topic, you are ready to search for scholarly information to see what the experts are saying about the topic you found in the popular sources. Using the Information Lifecycle, you can see that it takes anywhere from 6 months to a year for a scholarly resource to be published. Why? It has been reviewed by a panel of experts for authority, accuracy, and credibility. The reviewing process takes time, but some things are worth the wait. When your research is based on peer-reviewed journal articles, your research reflects those same expert qualities of authority, accuracy, and credibility.

Check out the video below to learn more about the Information Lifecycle.

(PfauLibrary, 2015)

Acknowledgements

The content for this module was drawn from the following sources:

Cabrillo College. (n.d.). Information literacy course in Canvas. https://cabrillo.instructure.com/courses/15592/modules

PfauLibrary (2015, January 9). Popular and scholarly sources: The information cycle [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-17MbjEws4

University of Toledo Libraries. (2020, March 13). Quality teaching & learning: Information literacy in Blackboard. https://libguides.utoledo.edu/QTL/blackboard

Know Your Audience

Popular, trade, and scholarly sources have different audiences in mind. Popular sources are intended for a general audience, one with no expertise or a deep understanding of the topic. Scholarly sources are written by professionals in a field of study for other professionals who are in, or going into, the same field. So scholarly research written by medical professionals is intended not for the general public, but for other medical professionals or medical students wanting to be doctors, nurses, technicians, etc.

Popular Sources

Usually, popular sources target a broad audience--anyone with a general interest in the topic. They are usually published in such a way as to draw the eye, with artwork, catchy titles, and lots of advertisements. These works are usually inexpensive (sometimes free) and are easily found in stores or online. Though popular communication is a very broad category and covers a number of sources, there are some common characteristics among these sources to help you identify them as popular communication.

Popular communication will generally:

-

- Be written by journalists, reporters, best-selling authors, bloggers, nearly almost anyone

- Contain news and entertainment articles, general interest topics, have no citations or bibliographies

- Use simple language

- Be published monthly, weekly, or even daily

- Be good for general information regarding a topic and for providing general overviews and common perspective on a given topic

Newspapers, such as The New York Times and The Washington Post, are popular sources. So are many magazines and books. Some examples of popular magazine titles are Time, Prevention, and Psychology Today.

Scholarly Sources

While popular communication is intended for a general audience, scholarly communication sources publish professional research and promote academic discussion among professionals. These resources are meant for students and researchers--scholars--who need or want an in-depth understanding or knowledge of an issue, problem, event, or topic. These sources are written by other scholars and researchers in order to provide new information and understanding in their field of expertise or to validate and confirm (especially in the sciences) the research of previous experiments. These articles are frequently long, often over 10 pages, and always include footnotes, bibliographies, or references. Scholarly articles are where the findings of research projects--the data and analytics--and case studies are first published, and even then, only after approval from either a journal's editor or, quite often, a peer-review.

During your college career, you will have many instructors who require "peer-reviewed" sources. What does this mean exactly? These journals undergo an extensive review process for accuracy and fairness before they are published. These reviews are conducted by professionals who are considered experts in the field, or "peers". So, these sources are often required by instructors because of the quality of content and research that they contain.

Scholarly communication has quite a few distinguishing characteristics. Here are some characteristics to look for to determine whether published materials are a form of scholarly communication.

Scholarly communication will generally:

-

- Be written by scholars, experts, and professionals in the field

- Have thorough and original research studies, have bibliographies and references, be generally unbiased

- Use complex and technical language related to the field

- Be published monthly, quarterly, or biannually

- Be good for statistics, data, research on a specific topic, and current research

Publications like Journal for Research in Mathematics Education and Nursing Science Quarterly are a couple of examples of scholarly communication. These publications have a specific audience in mind (professionals in the field) and are discipline-based.

Trade publications

There is actually one other type of communication that straddles the two extremes of popular and scholarly communication--trade publications. These can be magazines or journals, but they always focus on a particular profession (trade) and are written for people in that profession. They are often available through professional organizations, such as the American Institute of Certified Public Accounts, the American Medical Association, or the Society of Human Resource Management. Sometimes trade publications are included with membership, and members get automatic access to one or more of the publications when they join. Articles in trade publications focus on trends, news, and case studies for the trade. Staff writers and professionals in the trade write these articles in the language used in that trade, rather than for general audiences such as in popular sources, but articles are often shorter, thus less in-depth, and a bit less technical than scholarly articles, and they may or may not include footnotes, bibliographies, or references, depending on the preference of the publisher. Examples include Legal Week, Successful Farming, Communication Arts, and U. S. Banker.

Check out this brief video for a summary of the difference between magazines and scholarly journals:

(UARKLIB, 2008)

Finding Scholarly/Peer Reviewed Journals Online

You can find scholarly journal articles online. Here's how.

Using online databases provided by the library, you will find that search limiters allow you to select search results that are limited to scholarly/peer-reviewed journals. Search limiters can be found on the Advanced Search screen. Also, there are often boxes to check that will limit your search to "Scholarly (Peer-Reviewed) Journals" or just "Academic Journals". Look for the boxes and be sure to check them either at the beginning of your search or anytime during your search.

For example, here is a screenshot of the "Limit To" options in an EBSCO database:

The "Limit To" options are in the box on the left side, and the scholarly, peer-reviewed limiter is circled. Putting a check in the box next to "Scholarly (Peer-Reviewed) Journals" limits results to peer-reviewed journal articles. Interfaces will be different from database to database, but most interfaces will provide searchers with ways to limit results. This screenshot is just one example.

Acknowledgements

The content for this module was drawn from the following sources:

Cabrillo College. (n.d.). Information Literacy Course in Canvas. https://cabrillo.instructure.com/courses/15592/modules

UARKLIB (2008, September 26 ). Magazines and Scholarly Journals. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/2W3oPx3VedE

University of Toledo Libraries. (2020, March 13). Quality Teaching & Learning: Information Literacy in Blackboard. https://libguides.utoledo.edu/QTL/blackboard

Activity

Now that you know how to distinguish between popular, trade, and scholarly (peer-reviewed) sources, you will need to locate one of each type related to your research topic.

Either in the textbox in the LMS or on a Word document, do the following:

- Provide a link to each source type (Remember if your source is from a library database, you will need to provide the permalink, not the URL in the address bar). If your source does not have a link, you can take a picture of it to upload in the LMS.

- Write a sentence or two for each source indicating what makes it either a popular, trade, or scholarly source.

Copyright

All of the PALNI Information Literacy Modules are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Last Updated: Jun 9, 2025 3:32 PM

- URL: https://huntington.libguides.com/ILModules

- Print Page